History of DICKEY-john and Origins of Farm Automation

by William Lanphier Chapin, Sept 2018

The DICKEY-john Corporation of Auburn, IL was the first company to apply electronics to agriculture.

It’s moto in the 60’s through 80’s was “First in Agrionics”.¹

An abbreviated history of DICKEY-john is told on its present-day website.

http://www.dickey-john.com/history/

Please read their version first, and then come back here for,

as Paul Harvey calls it,

"the rest of the story".

The company version is not all together accurate or complete.

I am here to fill-in my personal perspective.

Their story is going pretty well in the first two paragraphs,

but stumbles through the critical period described in the second two paragraphs.

“After consulting with people who would become initial investors …”

Well, that would be my dad, Charles A. Chapin.

Chapin Farm

I grew up on a family farm in central Illinois ... Chatham, IL of Sangamon County to be more specific.

Central Illinois was and is still pervasive for three agriculural crops: corn², soybeans, and wheat.

(See the three crops depicted in the original DICKEY-john logo.)

My father was a third-generation attorney

practicing under his grandfather’s shingle in nearby Springfield, IL.

He occasionally received new clients from neighboring farmers

who needed a deed to land or a trust to divide their farm.

All the neighbors knew of him.

I recall the day, back when I was a five-year-old,

Bob Dickey came to the house and asked my dad for help

putting together a corporation and pursuing patents.

My dad was not a corporate or patent attorney,

but he knew just where to find the right advice.

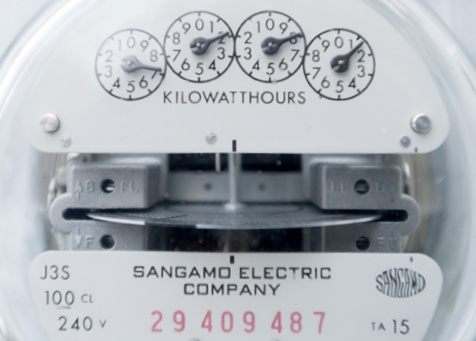

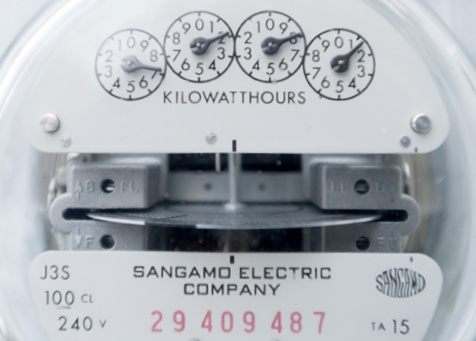

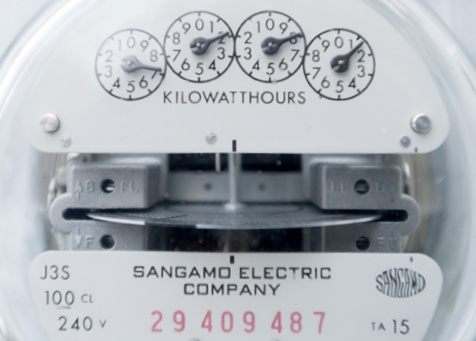

He was married to a Lanphier,

whose grandfather (Robert Carr Lanphier Sr.) had commercialized the electric meter in 1899

with founding of

Sangamo Electric Company

in Springfield, IL.

Sangamo and the Lanphiers

1966 was perfect timing for this connection.

A grandson of Sangamo Electric's founder was a staff electrical engineer and mid-level manager at the company

and was itching to move up into an executive role.

He also had the entrepeneurial genes.

Robert Carr Lanphier III (Bob) had paid his dues,

but Sangamo was mature and the executive roles were filled.

Upon meeting Dickey, Bob Lanphier immediately saw the possibilities

in not only this planting problem posed by Dickey,

but in all types of ways of leveraging sensors, electronics, and displays to solve farming efficiency problems.

Bob was able to convince his brilliant Sangamo colleague Jim Anson to help

him work nights and weekends on the idea.

The first office was in a cramped second-story quarter above a store-front on the corner of the square in Chatham.

I had just started elementary school a couple of blocks away

and would sometimes hang-out admire the "neato" electronics

while waiting for my mom to pick me up.

Soon Bob Lanphier and Jim Anson quit their day-jobs at Sangamo,

DICKEY-john got their own building down the block, still on the Chatham square,

and began production of planter monitors.

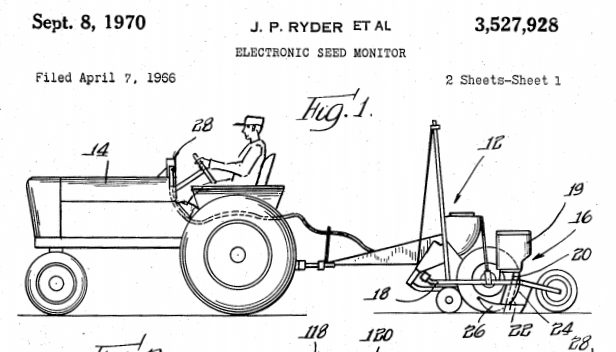

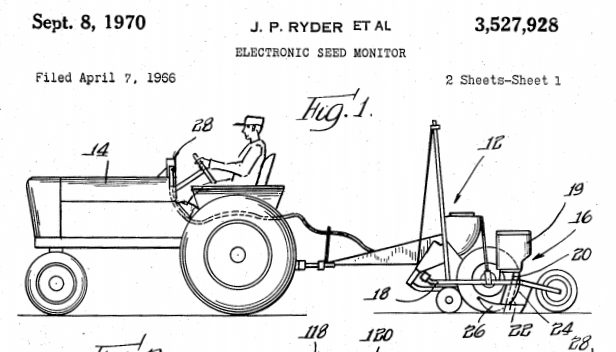

The original patent is a classic:

From the patent you can see that prior to finding Bob Lanphier,

Bob Dickey had worked Jim Ryder and Victor Sussia on the original invention.

Even though Bob Dickey had developed the idea and tickered with the invention

for years, the 1966 filing was critical.

J.I. Case filed an almost identical claim (US3537091A) in 1967,

likely just as DICKEY-john was entering the market.

My extended family and its financial colleagues

(The Bunns)

invested heavily in DICKEY-john.

My father was a board-member from its incorporation, through its IPO, until its sale into private ownership.

My grandfather (Robert Carr Lanphier Jr.) proactively bought hundreds of acres of farm land

in nearby Auburn, IL to use as test acreage.

I, through inheritance, now own some of that farm land today.

At some point around the IPO, date of which I cannot recall,

DICKEY-john purchased land from my grandfather and began building a plant

south of Auburn.

Amazingly, the facility shown in the contemporary image above

is the same foot-print as existed when I last worked on site in 1982.

The Internship

I had planned to spend the summer of 1979 mountaineering in Nepal,

having spent the summer of 1978 mountaineering in the Swiss Alps.

I committed a $500 deposit (earned from my cattle business) to reserve a spot on an expedition.

My parents had other thoughts and arranged with Jim Anson,

then Chief Engineer at DICKEY-john, to speak with me about an engineering internship.

DICKEY-john had interned the neighbor farm boys, Dave and Ron Steffen.

The Steffen boys went on to get EE degrees from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign,

where the inventor of the transistor guided students to invent the light-emitting diode.

The Steffen boys returned to work full-time at DICKEY-john and collectively authored dozens of patents.

My parents wanted me to follow that model.

At the time, I was a fresh high-school graduate,

committed to a liberal arts college in Minnesota

leaning towards a career in architecture.

Anson convinced me to drop my plans to conquer Everest and come check-out engineering.

He recognized my strong skills in drafting and assigned me to the mechanical design group.

Tedium

Initially I was given tedious tasks like propating change-orders through the documentation.

On harvesting days, I joined the dozen or so engineering interns in the awful task of following a

harvesting combine

around a wheat field collecting chaff.

DICKEY-john was trying to market a combine monitor that would detect the amount of seed loss.

By collecting the chaff, and hand-sifting it for seeds, we would count the actual seed loss

and thereby calibrate the sensors.

Separation

It did not take long before I seperated myself from the college engineering students.

My drafting board was in front of DICKEY-john's star designer Don.

He quickly became my mentor.

Upon my arrival, he was finishing-up the redesign of the radar horn for lower-cost manufacturing.

DICKEY-john patented the use of radar to gain "true ground speed" and

thus be able to accurately calculates the seeds per inch, planted in the ground.

Up to that date, DJ had produced perhaps a few dozen radar horns,

but they were to become a standard component of John Deere's planting systems.

Thus higher-quantity manufacturing had to be planned.

To complete the project

I volunteered to develop a cost-reduced design for mounting the radar horn.

This was low-risk to DICKEY-john, as the existing mounting bracket was a weldment

that required about 2 hours labor for each.

The welding crew was going to design a fixture to reduce the labor to an hour.

I chose investment casting, completed a design, and the cost was significantly reduced.

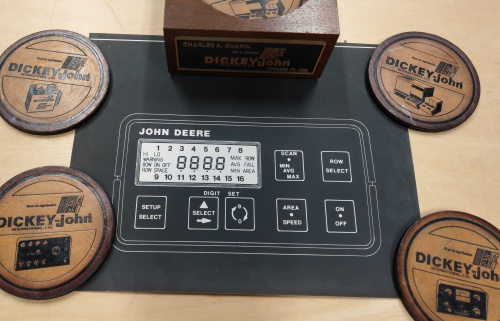

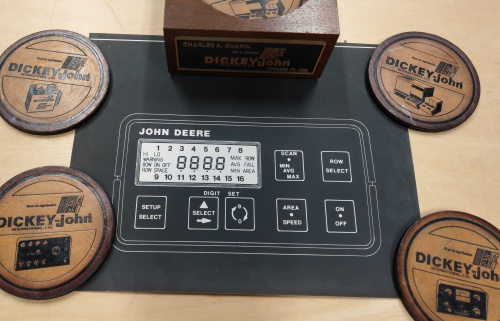

That summer Don was tasked with developing a line of new digital planter monitors under John Deere's brand.

John Deere's OEM product would appear on the market first, before DICKEY-john's own brand.

The previous DJ products were all in powder-coated steel cases.

This new John Deere product would be a clam-shell of injection-molded ABS plastic.

To help make Deere's aggressive timeline,

I off-loaded many of Don's tasks, including the front panel layout.

The front panel would be a laminate of two conductive circuits and a separator in between.

Once adhered to the blank front panel,

the product would have both graphics and a user-interface

sealed from the harsh environment of dust and rain.

Below is a shot of some of the few momentos from that summer:

coasters given to my father for board service and a image of my front panel layout.

International Harvester

International Harvester

DICKEY-john pleaded for my return for a second summer and assigned me a product management responsibility.

I was tasked at getting the OEM monitor for International Harvester into production.

The differences between the IH monitor and John Deere product of the previous year were entirely cosmetic,

and thus entirely on me.

The first month focused on the machining of tool and die for plastic mold injection.

Design and drawings had been mostly completed before my arrival.

I had to complete the design review with the customer and

ensure the fabricated tools followed the design without flaw.

I recall several trips to the International Harvestor's corporate offices in Hinsdale, IL

on the DICKEY-john corporate plane.

The product made it into production by the end of the summer.

Self-Driving Tractor

After a college summer in California, I returned to DICKEY-john for one final summer engineering internship in 1982.

I was able to join a project exploring the problem of self-driving tractors.

Prior to my arrival an engineer had outfitted a John Deere riding mower

with motorized steering and controller.

Other than a shutdown control, there was no throttle or transmission control.

GPS had not yet been launched for civilian use.

We experimented with different types of sensors and signals,

looking-in and looking-out from poles at the corners of the field.

For someone who had spent a significant portion of his lifetime to that point

tediously piloting a mower back and forth to maintain pastures,

it was one of the most exciting prospects.

Unfortunately, the ag economy was headed downward in the early 80's.

Family farms were failing at alarming rates,

despite the Carter-era farm bill hand-outs, subsidies, and buyouts.

Inflation and interest rates had risen off the charts

(fed rate was 20% in 1981).

Farmers could not afford capital equipment.

DICKEY-john decided to enact significant layoffs in June of 1982 in anticipation of a worstening economy.

Despite the fact that the engineering internship program

consistently proved to be DICKEY-john's best investment,

these temporary employees had to be terminated

prior to laying-off permanent employees to maintain labor morale.

Further, all research and development was cut, and thus the self-driving tractor project.

Epilog

Bob Lanphier focused efforts away from the US, which suffered from over-production,

and towards Asia, which under-produced.

Bread-lines were prevalent in the former Soviet Union.

The communist government began to admit the problem and invited American technologists

to come propose solutions to increase Soviet efficiency and production.

By 1986, Reaganomics had reduced interest rates from 20% to 5%,

and the Soviet Union appeared to falling.

Wall Streeters observed how Lanphier smartly kept DICKEY-john cash position

while expanding the international market.

They slowly began to acquire shares through the mid-80's lull.

In the 1987 board election, these investors managed to get several New Yorkers on the board.

In 1988, these now-insiders came to the table with a hostile takeover in the form of a

leveraged buyout (LBO).

LBO's were in a boom in the 80's.

The DICKEY-john executive staff felt this would be a disaster for people of DICKEY-john.

They quickly scrambled for a "white knight".

Bob Lanphier found one in the Minneapolis-based Churchill Industries.

The published DICKEY-john history states:

"Under their guidance, DICKEY-john has embarked on a new era

of strategic product development and quality initiatives with key customers."

I will agree that Churchill has been an excellent custodian.

But the "new era" in product development has meant a major slow-down.

DICKEY-john is no bigger now than in its Lanphier hay-days.

They sell the same range of products:

planting monitors, implement monitors, application control,

moisture testers, and grain analysis computers.

Yes, they have implemented GPS, but that is no longer rocket-science.

Yes, they have achieved ISO 9001, but the Lanphier leadership maintained excellent quality control,

and had the standard existed at the time, it would have been ISO.

Footnotes

-

Agrionics: Of course, one is going to be the first at something that they coined and trade-marked.

When DICKEY-john was taken private in 1988, the trade-mark was dropped and now is used in India and Pakistan.

-

Corn should be differentiated into "field-corn" and "sweet-corn".

Most of us think of "sweet corn" which is served both on the cob and as a vegatable on the plate.

99% of all corn produced is "field-corn" which is used in corn-meal

and feed for chickens, hogs, and cattle.

Return to WLC -> Projects

International Harvester

International Harvester